South American authorities are considering their next move on the heels of the French government’s recommendation that 30,000 French women have their silicone breast implants, manufactured by Poly Implant Prothese (PIP), removed. The now-bankrupt French implant manufacturer is facing criminal charges as its chief executive is on the lamb, wanted by Interpol and Costa Rican authorities for crimes involving “life and health.”

South American authorities are considering their next move on the heels of the French government’s recommendation that 30,000 French women have their silicone breast implants, manufactured by Poly Implant Prothese (PIP), removed. The now-bankrupt French implant manufacturer is facing criminal charges as its chief executive is on the lamb, wanted by Interpol and Costa Rican authorities for crimes involving “life and health.”

Tens of thousands of women in over 65 countries around the world have the same implants, made from industrial rather than medical quality silicone. The implants are also said to be at an unusually high risk for rupture. Most of the women having received the PIP implants live in South America and western Europe.

The implants are particularly widespread in Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia and Argentina across different economic levels, with many young girls eager to augment their bust size before they become adults.

In Brazil, a National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) spokesperson said that it “has not yet made a recommendation,” echoing the sentiments of health professionals and officials in other Latin American countries. He states that the French government also recognized an as of yet unproven cancer risk to ruptured PIP implants.

“The medical facts that we know suggest that these implants can rupture earlier and with a greater risk of inflammatory reaction,” said Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery president Jose Horacio Aboudib.

Aboudib said his group in Brazil recommended that women who received the implants get tested early to make sure the implants were viable.

Venezuela’s union of plastic surgeons agreed, declining to recommend that women with the PIP implants get them removed, recommending preventative checkups instead. About 40,000 breast augmentations are performed in Venezuela each year, and plastic surgery is widespread in a country that has produced regular top contenders for Miss Universe over the years.

Argentina’s ANMAT drugs authority urged 15,000 women who received implants to “consult” their doctors.

In Colombia, implants are sometimes offered as birthday gifts, especially for “quinceaneras”–girls’ 15-year-old birthdays–that mark a girl’s passage into young womanhood.

“Drug traffickers also offer the surgery as a gift to their girlfriends,” said surgeon Celio Bohorquez, spokesman of the Colombian Society of Plastic Surgery.

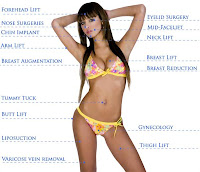

This cosmetic surgery scandal is multiplied exponentially by the hordes of women who have run to surgical enhancement over the last couple decades. It really put the practice into its massive perspective, as we see the scare affecting up to 300,000 women in over sixty countries.

This cosmetic surgery scandal is multiplied exponentially by the hordes of women who have run to surgical enhancement over the last couple decades. It really put the practice into its massive perspective, as we see the scare affecting up to 300,000 women in over sixty countries.

The surprise to me is in the brazenness PIP showed in its safety protocols and practices. I recommend that all women suspecting that they may have silicone breast implants manufactured by PIP to call their surgeon to discuss removal options and risks. Once again, my sympathies to any and all involved.