How does it feel to be a human medical guinea pig, part of vast research project to determine whether ADHD is a true medical condition or not? And also to determine whether the current prescribed treatment—pharmaceutical speed—is a valuable treatment option for said potential disorder? Forget that the researchers (scientists, doctors, politicians, school officials, teachers, parents) have already made up their minds before the results have come in—that’s today’s medical research, philosophy and practice whether you like it or not. But how does it feel that your children are the ones being indiscriminately tested on? Oh wait…you don’t believe me…ah, I see…well then:

How does it feel to be a human medical guinea pig, part of vast research project to determine whether ADHD is a true medical condition or not? And also to determine whether the current prescribed treatment—pharmaceutical speed—is a valuable treatment option for said potential disorder? Forget that the researchers (scientists, doctors, politicians, school officials, teachers, parents) have already made up their minds before the results have come in—that’s today’s medical research, philosophy and practice whether you like it or not. But how does it feel that your children are the ones being indiscriminately tested on? Oh wait…you don’t believe me…ah, I see…well then:

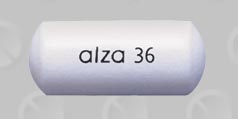

A recent study now suggests that Ritalin and other speed drugs regularly fed to children might cause long-term brain changes. You don’t say? Gosh, I recall some quack with a blog reporting that vociferously over the last few years… Yes, according to the study, users of methylphenidate (most commonly sold as Ritalin) had higher levels of a protein called the dopamine transporter in their brains after one year of treatment compared to before they starting taking the drug. And these increased levels may lead to future drug tolerance, and get this…”could result in more severe inattention”!

Scientists have speculated that people with ADHD naturally have more dopamine transporters in their brains, but according to study researcher Dr. Gene-Jack Wang, of Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y., the new study suggests that the increase comes from the drug treatment itself and is not associated with the so-called condition alone. Prior to the study, none of the participants had ever been treated with ADHD drugs.

Scientists have speculated that people with ADHD naturally have more dopamine transporters in their brains, but according to study researcher Dr. Gene-Jack Wang, of Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y., the new study suggests that the increase comes from the drug treatment itself and is not associated with the so-called condition alone. Prior to the study, none of the participants had ever been treated with ADHD drugs.

Even scarier is that this study only looked at the effects following one year of speed medication therapy. It is unknown what the longer-term effects might be. Do you still feel good about subjecting your kid to an ongoing medical study?

Among study participants, a 24% increase in the number of dopamine transporters was found in some areas of the brain, while there was no increase in dopamine transporters in a group of healthy participants who did not take Ritalin.

So my question to parents is, “Why?” Why do some of you so unquestioningly trust the authority of a profession that treats with dangerous drugs first, does research later? Isn’t anyone else out there uncomfortable with the notions of, “We believe that possibly…,” “We think it might…,” and other rationalizations of uncertainty when it comes to the health of your children? I would never, ever, ever subject my child to drugs because some arrogant professionals tell me that they “believe it might help.” Sorry but that’s sloppy parenting.

So my question to parents is, “Why?” Why do some of you so unquestioningly trust the authority of a profession that treats with dangerous drugs first, does research later? Isn’t anyone else out there uncomfortable with the notions of, “We believe that possibly…,” “We think it might…,” and other rationalizations of uncertainty when it comes to the health of your children? I would never, ever, ever subject my child to drugs because some arrogant professionals tell me that they “believe it might help.” Sorry but that’s sloppy parenting.

Unfortunately, too many people still consider medical science their ultimate health authority. No doubt, modern medicine does some pretty incredible things, but I am not placing my faith in a practice and industry that often acts before it knows…not when it comes to the health of me and my loved ones. Yes, I am offended by the modern medical approach to what I have so openly called a “non-condition.” ADD is NOT a disorder. We all have it when we are forced to endure something that doesn’t inspire us. Drugging our children because we can’t understand how to tap into their inspiration is not the answer. Hopefully this study is the beginning of the end to this massive public guinea pig project…but I doubt it.