To be sure, everything has an upside. Take Tourette syndrome: A recent study has shown that children with the neurological tic disorder perform better on cognitive motor control tests than children without the disorder. You don’t say? Yes, the children with Tourette’s showed less impulsivity of movements and greater cognitive control–that is, they were less likely to act without thinking.

Tourette syndrome (TS) is characterized by repetitive, involuntary movements and vocalizations called tics. The first symptoms of TS are almost always noticed in childhood. Some of the more common tics include eye blinking and other vision irregularities, facial grimacing, shoulder shrugging, and head or shoulder jerking. Perhaps the most dramatic and disabling tics are those that result in self-harm such as punching oneself in the face, or vocal tics including coprolalia (uttering swear words) or echolalia (repeating the words or phrases of others).

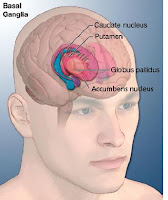

Researchers believe that the enhanced motor control stems from structural and functional brain changes that likely result from the need to constantly suppress tics. According to one of the study’s authors, Stephen Jackson of the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, MRI exams confirmed that the “Tourette’s brain” showed changes in the white-matter connections that allowed different brain areas to communicate with each another.

Pretty amazing how the human brain compensates for disruptions in one area by tightening up the function of another. If you can’t see the benefit of increased cognitive motor control, then you can’t see the downside to Tourette’s either, because they are two sides of the same coin. Anybody that knows human physiology knows that the body will do what it needs to survive. An anastomosis is a connection of blood vessels serving as backup routes for blood to flow if one link is blocked or otherwise compromised. The body does this all the time, and I see the connections here in this recent Tourette’s study.

Pretty amazing how the human brain compensates for disruptions in one area by tightening up the function of another. If you can’t see the benefit of increased cognitive motor control, then you can’t see the downside to Tourette’s either, because they are two sides of the same coin. Anybody that knows human physiology knows that the body will do what it needs to survive. An anastomosis is a connection of blood vessels serving as backup routes for blood to flow if one link is blocked or otherwise compromised. The body does this all the time, and I see the connections here in this recent Tourette’s study.

The researchers believe that the significance of these findings is that it may help explain why some people with TS who have profound tics during childhood are relatively tic-free by early adulthood, while others continue to have severe tics throughout their life. They also point out the potential benefits from “brain training” techniques that help people with TS gain control of their symptoms.

The researchers believe that the significance of these findings is that it may help explain why some people with TS who have profound tics during childhood are relatively tic-free by early adulthood, while others continue to have severe tics throughout their life. They also point out the potential benefits from “brain training” techniques that help people with TS gain control of their symptoms.

Absolutely. From what we know about neuroplasticity, along with these findings, it seems reasonable that new pathways can be created, benefiting people with TS. My feeling is that will be seeing more therapeutic work involving brain training not just with Tourette’s but with other neurological disorders, like autism, in the near future.